At first glance, it looks like a skinned cat or dog, perhaps even a suckling pig hanging outside a roadside restaurant. On closer inspection, it could be the corpse of a mutant creature from the depths of David Cronenberg's imagination. It is, in fact, a beer bottle that has been fused into a misshapen, almost muscular, form by the unimaginably intense heat of a nuclear blast.

Shomei Tomatsu's most well-known photograph, simply entitled Melted Bottle, Nagasaki, 1961, is also one of his most surreal. It was taken while he was on a magazine assignment to photograph the reconstruction of the devastated city. Tomatsu, then 31, had, like many Japanese people, chosen not to confront the trauma of Nagasaki, but what he found there made him rethink his attitude to his country's history as well as to photography. He set out to try and record a city that, like the country as a whole, was intent on building its future while wiping out many traces of its past.

The melted bottle was just one of several sad, strange relics of the atomic devastation that he found on display in a small museum of remembrance, which Tomatsu wandered into on one of his many walks around Nagasaki. He immediately recognised the object's power and mystery. Like many of his most powerful images, Melted Bottle possesses a strange, almost dreamlike power that intrigues and unsettles, taking the viewer into an unfamiliar terrain far beyond the parameters of reportage. He also photographed a wristwatch whose hands were frozen at 11.02am on 9 August 1945, the moment the A-bomb exploded, and the blasted remains of statues of angels from a Christian church in the city.

The American curator and critic Leo Rubenstein described Tomatsu's Nagasaki photographs as "sad, haggard facts", noting that, as Tomatsu wandered with his camera, "beneath the surface there was a grief so great that any overt expression of sympathy would have been an insult." Tomatsu did, though, summon up the lasting horror of Nagasaki in portraits of the dreadfully scarred skin of survivors of the blast – pictures that suggest the psychological as well as physical cost of the nuclear attack.

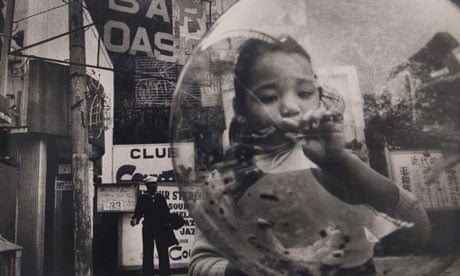

Though still relatively unknown outside Japan, Tomatsu, now 80, is arguably the greatest and most influential of all the photographers that emerged during his country's turbulent postwar era. Over a span of 50 years, his work has reflected, often obliquely, the changes in Japanese culture as the American military presence and then the unstoppable spread of American popular culture, helped shaped a new outward-looking, consumer-driven nation. Two series of photographs – Protest, Tokyo, 1969 and Eros, Tokyo, 1969 – record the often turbulent youth cultural changes of the time. His book, Oh! Shinjuku, named after a shopping district in central Tokyo, chronicles the rise of a young and rebellious Bohemianism that, as an older outsider, he saw – as he later put it – "through the eyes of a stray dog".

Those words seem prophetic. Tomatsu was one of the giants of Japanese photography that a younger generation of photographers who came to prominence in the late 60s reacted against. Known as the Provoke Movement, after the magazine that published their work, it included Daido Moriyama, Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki. In its founding statement of intent, Taki wrote: "We photographers must use our own eyes to grasp fragments of reality far beyond the reach of pre-existing language, presenting materials that actively oppose words and ideas ... materials to provoke thought." Forty years on, though, Tomatsu's radical approach – his freeform, expressionist style, odd camera angles, strange cropping and framing – has been reappraised and he is now seen, ironically enough, as one of the pioneers of the Provoke era. What he makes of all this is anyone's guess; he is famously reclusive and has never ventured outside Japan.

In 2006, a retrospective of Tomatsu's work, entitled Skin of the Nation, was held at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, shocking and enthralling many visitors who were unfamiliar with his work, its shifts in style and subject matter as well as its double-edged treatment of Japanese traditions and symbols. Alongside Nagasaki and its traumas, Tomatsu's abiding subject is the collision of the east and the west, and the cultural – and moral – tremors that resulted. For all these reasons, his work is complicated and even contradictory. Often, for instance, Tomatsu pointed his camera down at the earth itself, capturing the debris and detritus of humanity: a shoe embedded in mud, a discarded cigarette end. The runic imprints of human activity – and time itself – on asphalt and tarmac.

In all of this, Tomatsu transformed the very idea of photography in Japan. His willingness to take formal and emotional risks reverberates to this day in the work of his great friend and admirer, Daido Moriyama and in the often explicit imagery of Nobuyoshi Araki.

It was Moriyama who noted Tomatsu's "awesome tenacity" in following his photographic vision, but that vision is awesome, too, in its range. He is a capturer of life in all its intense, often baffling, intimacy; a visionary who looked anew at skin and sky, earth and street, hair and concrete, as well as all manner of ephemeral-seeming things. His camera caught and remade them all.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion